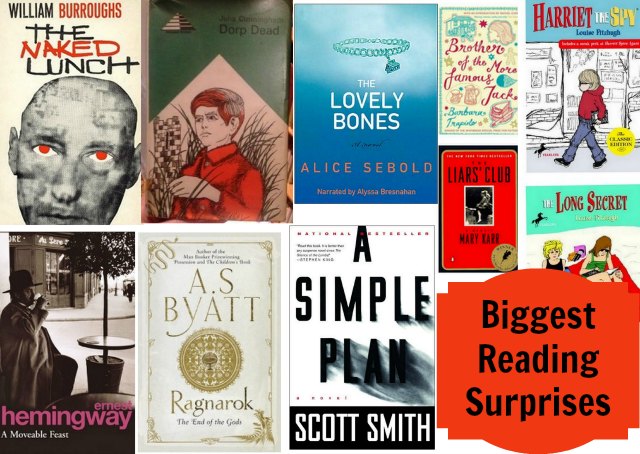

If the buzz over last week’s infamous ‘Red Wedding’ episode of Game of Thrones has anything to teach us, it’s how much people love a good surprise. But those of you were listening really carefully, if you could hear anything over the internet screams and memes of shock and YouTube films of people’s reactions, if you could get past all that there was something else … you would’ve heard the collective snorting of those people who’ve already read the books, knowing full well what was about to happen. After being questioned about what he thought about the reaction, George R R Martin himself waded into the furore by wryly quoting a comment he read about how now everyone knew why all their ‘nerdy friends’ were depressed when that book first came out.

I’ve been thinking about this post for a long time, and this example is just one of countless I can think of that demonstrates the lingering power a story can wield over us; the machinations of plot coming together, successful characterisation, these things writers strive to nail. When it happens, it’s magic. The reader is invested, we’re hooked. Not always out of love or admiration; sometimes its out of begrudging respect or the resolution to see a thing through to the end. These are the experiences that bring us back to reading. In my Island essay last year, I told the story of a customer in my local bookshop who was a self-confessed ‘non reader’ and wanted to buy 50 Shades of Grey “to see what the fuss was about”. To the store owner’s surprise, this same customer returned a short time after to buy Anna Funder’s All That I Am because she wanted to give her mind “something valuable”. She’d caught the reading bug.

This is what narratives do that touch me, they give me something valuable to consider and mull over. They make me want to keep creating my own and lately, in this reflective frame of mind, I’ve been asking my writer and reader friends a question: what has been their biggest reading surprise? Akin to putting book down once it was finished and going, ‘That was not what I was expecting.’ Happily, they’ve taken the time to answer.

Ragnarok

I read A.S. Byatt’s Ragnarok in the right month. Earlier, I had stuffed myself with Norse sagas and myths, including the Völuspá, which foretells the apocalypse: Ragnarök. I also read Marvel comics’ Thor, and got a buzz from the hero’s archaic, courtly brutality.

But the star of Byatt’s Ragnarok is not golden-boy Odinson, but his enemy: Jörmungandr, the World Serpent. The snake is all appetite. Jörmungandr has “flesh-fronds streaming back from her sharp skull, her fangs glinting.” Byatt’s alliteration is enchanting.

Byatt’s serpent, gorging and swelling, and growing to feed, is an unsettlingly familiar vision of modern life. The vision has lingered.

Damon Young is a philosopher and author. His latest book is Philosophy in the Garden (MUP, 2012), which will be published by Random House UK in 2014. Damon is now writing a book on exercise and philosophy for Pan Macmillan UK, and two children’s books for UQP.

Dorp Dead

I first read Dorp Dead by Julia Cunningham at age 11, and it wins the prize for my longest-term freakout over a children’s book. Gilly is left an orphan after the death of his grandmother, and he craves a life of quiet and order that living with hundreds of other boys in an orphanage just can’t provide. His pretense of stupidity (despite being ‘brilliant’) is ensured by his deliberately never learning to spell. When Gilly is sent to live with Kobalt, the town ladder-maker and eccentric, it seems as if his prayers have been answered. Kobalt’s life is lead in a series of precise hourly rituals, and while Gilly at first slides into the grooves of this ordered life with relief, the oppressive routines and looming threat of violence (Kobalt beats his dog so it will “learn to die”) make him increasingly uneasy. For me, Gilly’s insidiously gradual loss of self was terrifyingly unexpected to experience in a junior fiction book – though I couldn’t pinpoint at age 11 that this was what frightened me, it still left a huge impression.

Anna Ryan-Punch is a poet, reviewer and librarian. Her blog is four hundred years ago, a baby went to sleep and is @ARPy_ on Twitter.

A Moveable Feast

I have read a lot of Hemingway in my time. Much of it involves men being men, or at least, some strange approximation of it. It’s common to find them hunting, fishing, destroying intimacy, drinking, and generally behaving in an appalling manner. With A Movable Feast, Hemingway finally came clean. He’d once loved sitting at Parisian cafes writing, wandering, and reading tomes from the iconic Shakespeare and Company. Included here are his relationships with F. Scott Fitzgerald, Getrude Stein and Ezra Pound. The depiction of Hemingway’s time in Paris is naturally doctored to flatter him, as he was a writer, after all. Regardless, I was impressed with the level of compassionate reflection so often present within the book’s 192 pages.

Laurie Steed is a writer, reviewer and PhD student. His blog is The Gum Wall and is @lauriesteed on Twitter.

The Lovely Bones

I think one of my biggest reading surprises came at the beginning of a book, not the end. The opening lines of Alice Sebold’s The Lovely Bones: My name was Salmon, like the fish; first name, Susie. I was fourteen when I was murdered on December 6, 1973. I thought, ‘Hmmm, where do we go from here?’ and expected a really depressing read. But it wasn’t. Sad, a bit overly sentimental in places, but overall just a lovely, lovely book. I have never seen the movie – I couldn’t see how it could possibly live up to the book.

As an aside, I’d love to write an opening like that!

Allison Tait is a writer and journalist and blogs at Life in a Pink Fibro and is on Twitter @altait Her first novel will be published in 2013.

Authors Barbara Trapido and Mary Karr

Many of my biggest reading surprises have come from library books. Browsing library shelves, I feel a different urge to the one I do in bookshops, where I’m inevitably drawn to the latest talked-about thing. In a library, I’m drawn to the authors I’d always been curious about but never tried, or pick up books I like the sound of, but know nothing about. That’s how I discovered two of my all-time favourite writers: UK novelist Barbara Trapido, who writes like a kind of bohemian Jane Austen, and US poet and memoirist Mary Karr, who grew up with crazy parents in Texas (her mother once stood over her with a knife, and had six husbands), became an alcoholic on the east coast literary scene (now recovered) – and writes beautifully about it all. Both authors have become touchstones for me of what writing can be, at its best – and their books are ones I revisit as I would a treasured friend.

Jo Case is the author of Boomer and Me: A Memoir of Motherhood, and Asperger’s (Hardie Grant) and senior writer/editor at The Wheeler Centre. She occasionally blogs at www.jocasewrites.com/blog.

A Simple Plan

The North-shore hermit that I was had been invited to a colleague’s NRL Grand Final party somewhere in Sydney’s outer western reaches and such was my trepidation that I managed to leave home without an ever-present book. A newsagent’s kiosk at Central station provided some hope in the form of trashy trade paperbacks and with my train arriving all too soon, I alighted upon a lonesome plain cover that carried surely the peak-blurb of endorsements … “simply the best suspense novel of the year” – Stephen King.

Don’t ask me what occurred at the party or even who won the game that year (’94) for all I had eyes for were the on-rushing pages – friends in the woods finding a downed light aircraft containing gym-bags stuffed with millions of dollars in cash, how they agreed to divide and keep the money hidden for at least a year and then the slow but sure burn as this simple plan first unravelled, placing mortal consequences on to quotidian decisions, before escalating darkly as the tension wound to such a point that I confess I had to stop reading.

The reason this book still resonates after twenty years is how well the surface narrative compels the reader on, despite undercurrents of the plot’s obviousness – my surprise being that it’s the only book I’ve ever had to stop reading because of the nervous tension it generated: less a series of suspenseful twists, rather a highly-strung Möbius strip of a book.

Jim Collings is @caldron_baidu on Twitter and is a true gentleman of the internet. He can be found at Goodreads.

Naked Lunch

I remember reading William S. Burrough’s Naked Lunch as a late teen and being incredibly bored by it and surprised not just by my boredom but a strange sense of shame at seeking out drug literature so desperately, despite it being pretty common for late teens. Naked Lunch is deeply weird, but weirdly dull, and that seems partly deliberate. I was also surprised to find that I was much more taken with the court transcript around the censorship trial that served as an appendix, and so began a lifelong love with the story behind books rather than the books themselves. Useless!

Sam Twyford-Moore is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. He is the Director of the Emerging Writers’ Festival. The Emerging Writers’ Festival will be travelling to Tasmania for its roadshow on 31 October – 2 November.

Harriet the Spy

Memory is a strange thing. Things we remember and forget seem too arbitrary. Most puzzling of all is the false memory, because I would have sworn under oath I read this book when I was a kid. And yet nothing about Harriet the Spy (apart from the central trope – child spy writes secret stuff in notebook, gets caught when kids read her notebook) was familiar to me. Not the voice, or the mood, or the setting, or the characters, or the content of the secret stuff. Certainly not Harriet herself. This book is DARK. More than once, Harriet comes home from school, gets in the bath, and cries and cries. Harriet is surely on the autism spectrum. Harriet (mild spoiler) refuses to apologise for most of the book, and when she does, she fakes it because she’s not actually sorry or ashamed. Her mentor, Ole Golly tells her, “Sometimes you have to lie. But to yourself you must always tell the truth.” Harriet is rich, privileged, and almost impossible to like. She is more antihero than a hero. And yet, somehow this book is brilliant. Even more surprising was the almost forgotten sequel, The Long Secret. Periods! Religion! Malaise! And a secret hidden in plain sight. Harriet is not the star of this book but the sidekick, however the conversations Harriet has with her father as she continues her journey through the complexities of human attachment and behaviour are extraordinarily beautiful.

Penni Russon is an author and her latest novel Only Ever Always will be released in the United States in July. She is teaching a course about writing for young adults at Writers Victoria, also in July.

And me?

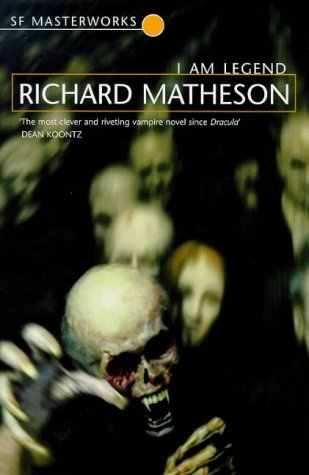

I am Legend

This is the edition of I am Legend I borrowed from the library. With a cover like that, you can see why it caught my attention! I pulled it down to ‘give it a go’ (I thought to myself, optimistically). Here’s the opening paragraph: “On those cloudy days, Robert Neville was never sure when sunset came, and sometimes they were in the streets before he could get back.” Pretty soon you discover the ‘they’ are vampires, they’re all trying to eat him, and Robert is in a bit of a bind because he’s the (apparent) last human on earth. Matheson’s style is pared-back; this narrative distance makes the lean novel – if anything – even more disturbing, its conclusion even more upsetting. A novel not without its critics, but I remember reading it when one of the kids (I forget which!) was a baby. And for me, a new, tired mum, to give up my sleep meant it was pretty damn good. A total surprise.

Thank you to everyone for your contribution!

What’s been your biggest reading surprise? Let me know in the comments.